Taxpayer Democracy, for Each Taxpayer

Today, the day American taxpayers wonder if the federal government is really worth all the money and hassle, I have an article at the Washington Post on how to give taxpayers more control.

Why shouldn’t taxpayers make direct decisions about how much money they want to spend on other government programs, like paying off the national debt, the war in Iraq or the National Endowment for the Arts? This would force the federal government to focus time and resources on projects citizens actually want, not just efforts that appeal to special interests.

To do this, we’d have to expand the concept of the campaign financing checkoff to all government programs. With this reform, the real expression of popular democracy would take place not every four years but every April 15. A new final page of the 1040 form would be created, called 1040-D (for democracy). At the top, the taxpayer would write in his total tax as determined by the 1040 form. Following would be a list of government programs, along with the percentage of the federal budget devoted to each (as proposed by Congress and the president). The taxpayer would then multiply that percentage by his total tax to determine the “amount requested” in order to meet the government’s total spending request. (Computerization of tax returns has made this step simple.) The taxpayer would then consider that request and enter the amount he was willing to pay for that program in the final column–the amount requested by the government, or more, or less, down to zero.

A taxpayer who thinks that $600 billion is too much to spend on military in the post-Cold War era could choose to allocate less to that function than the government requested. A taxpayer who thinks that Congress has been underfunding Head Start and the arts could allocate double the requested amount for those programs….

Real budget democracy, of course, means not just that the taxpayers can decide where their money will go but also that they can decide how much of their money the government is entitled to. Thus the last line on the 1040-D form must be “Tax refund.” The form would indicate that none of the taxpayer’s duly calculated tax should be refunded to him; but under budget democracy the taxpayer would have the right to allocate less than the amount requested for some or all programs in order to claim a refund (beyond whatever excess withholding is already due him).

I regret that space considerations required the loss of my historical context:

Ever since Magna Carta, signed 800 years ago this spring, the Anglo-American tradition of fiscal policy has been that the people would decide how much of their money they would give to government. Parliament arose as a representative body to which the Crown would appeal for funds. The monarch had to explain why he or she was seeking more funds–and Parliament frequently rejected the request as frivolous, wasteful, or actually injurious to the commonweal.

Today, of course, we can’t count on the legislative branch to guard our tax dollars, and technology makes it easier for us to direct them ourselves.

More on taxes – and Magna Carta – in The Libertarian Mind. Find ideas for government programs that are unnecessary or too big at Downsizing the Federal Government.

Posted on April 15, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

We Should Get to Decide How the Government Spends our Taxes

In his 1992 Republican National Convention speech, President George H. W. Bush proposed letting taxpayers commit up to 10 percent of their payment to reducing the national debt. The proposal never went anywhere, but it points to a good idea: Taxpayers should be able to designate how their tax dollars are spent. Already, we allow for this in very limited ways. A check-off at the top of the 1040 form invites every taxpayer to direct $3 of their federal tax to the Presidential Election Campaign Fund (only 6 percent of taxpayers do). In Virginia, my VAC invites me to contribute additional funds to more than 100 organizations ranging from the Democratic and Republican parties to the U.S. Olympic Committee, the Virginia Arts Foundation, and many local school and library funds.

Why not take this one step further? Why shouldn’t taxpayers make direct decisions about how much money they want to spend on other government programs, like paying off the national debt, the war in Iraq or the National Endowment for the Arts? This would force the federal government to focus time and resources on projects citizens actually want, not just efforts that appeal to special interests.

To do this, we’d have to expand the concept of the campaign financing checkoff to all government programs. With this reform, the real expression of popular democracy would take place not every four years but every April 15. A new final page of the 1040 form would be created, called 1040-D (for democracy). At the top, the taxpayer would write in his total tax as determined by the 1040 form. Following would be a list of government programs, along with the percentage of the federal budget devoted to each (as proposed by Congress and the president). The taxpayer would then multiply that percentage by his total tax to determine the “amount requested” in order to meet the government’s total spending request. (Computerization of tax returns has made this step simple.) The taxpayer would then consider that request and enter the amount he was willing to pay for that program in the final column–the amount requested by the government, or more, or less, down to zero.

“The case for letting taxpayers choose whether their money goes to schools or the police or Medicaid.”

A taxpayer who thinks that $600 billion is too much to spend on military in the post-Cold War era could choose to allocate less to that function than the government requested. A taxpayer who thinks that Congress has been underfunding Head Start and the arts could allocate double the requested amount for those programs.

There would be quite a bit of debate, of course, over how to list programs in the 1040-D program. Spending interests would want to use broad categories–national defense, health, education, job training. Opponents of spending would prefer to narrow the categories so taxpayers can see what they’re really buying– defense of Japan and Korea, war in Iraq, farm subsidies, mass-transit “demonstration” projects in West Virginia, and so on. Libertarians and the arts establishment might agree on listing just “arts,” while the religious right might lobby to have the category broken into “fine arts,” “pork-barrel arts,” and “obscene art.” Language would be an issue — “corporate welfare” or “loans for small businesses”?

Real budget democracy, of course, means not just that the taxpayers can decide where their money will go but also that they can decide how much of their money the government is entitled to. Thus the last line on the 1040-D form must be “Tax refund.” The form would indicate that none of the taxpayer’s duly calculated tax should be refunded to him; but under budget democracy the taxpayer would have the right to allocate less than the amount requested for some or all programs in order to claim a refund (beyond whatever excess withholding is already due him).

Entitlements would be the biggest problem. About 60 percent of the federal budget now goes to entitlement programs. Medicare and Medicaid make up more than 20 percent of spending, and most of that comes from general revenues. Should taxpayers be able to withhold their hard-earned dollars from such programs? In a free society, they should. So how do we handle a shortage of funding? Congress could change the spending parameters to fit what the taxpayers are willing to supply. The budget democracy process could also include a provision allowing Congress by a two-thirds vote to override the taxpayers and insist on larger payments to pay for entitlements or other services deemed essential.

Then, instead of trying to decide which candidate might be telling the truth about his commitment to fiscal responsibility, the taxpayers could take matters into their own hands, finally being able to say effectively, “You’re spending too much. We’re cutting your budget.”

Posted on April 15, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

More on Krugman’s Missing Libertarians

I wrote last week about Paul Krugman’s claim that “there basically aren’t any libertarians” because “There ought in principle, you might think, be people who are pro-gay-marriage and civil rights in general, but opposed to government retirement and health care programs — that is, libertarians — but there are actually very few.” I offered some evidence from Gallup, Pew, and other polls that in fact there are substantial numbers of voters who hold libertarian-ish views on both economic and social issues.

Bryan Caplan runs some regressions to find that voters’ positions on a variety of issues don’t line up the way Krugman assumes they do. Ilya Somin explores various problems with Krugman’s claims, including this:

It’s also possible to try to justify Krugman’s claim by arguing that most of those people who hold seemingly libertarian views haven’t thought carefully about their implications and are not completely consistent in their beliefs. This is likely true. But it is also true of most conservatives and liberals. Political ignorance and irrationality are very common across the political spectrum and only a small minority of voters think carefully about their views and make a systematic attempt at consistency. Libertarian-leaning voters are not an exception to this trend. But it is worth noting that, controlling for other variables, increasing political knowledge tends to make people more libertarian in their views than they would be otherwise.

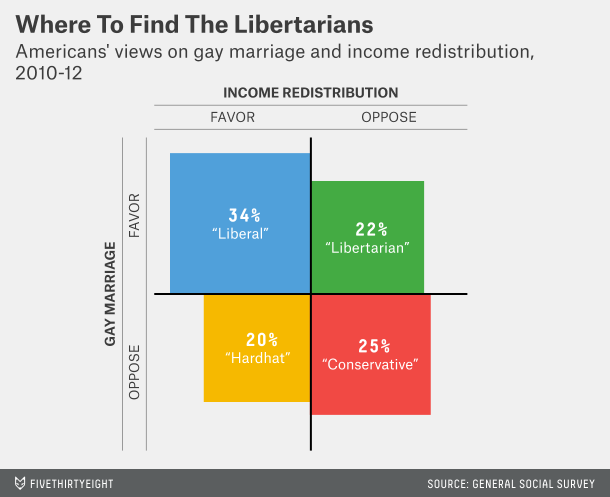

Nate Silver, Krugman’s erstwhile New York Times colleague who now runs the FiveThirtyEight website, writes, “There are few libertarians. But many Americans have libertarian views.” He notes:

If Krugman is right, you should see few Americans who are in favor of same-sex marriage but oppose government efforts to reduce income inequality, or vice versa.

As it turns out, however, there are quite a number of them; about 4 in 10 Americans have “inconsistent” views on these issues.

Not actually inconsistent, of course, just not consistently “liberal” or “conservative.” Those “inconsistent” Americans just might be consistently libertarian or anti-libertarian. Silver has a nice matrix, grounded in data from the General Social Survey unlike Krugman’s off-the-cuff matrix:

On those two issues, the largest group take liberal positions on both. Substitute different issues – cutting taxes, say, or internet censorship – and you’d get larger numbers of libertarians. But whatever set of issues you choose, you’re likely going to find significant numbers of voters taking positions that don’t fit into Krugman’s two boxes.

Silver speculates on why there seems to be so little political representation for these large groups of voters:

…the hard-core partisans who vote in presidential primaries are much more likely to take consistently liberal or conservative positions than the broader American population, as Krugman’s colleague Nate Cohn points out.

And the parties themselves — who have disproportionate influence in the primaries — have highly partisan views by definition. Almost all voting in the U.S. Congress, on social issues and economic issues alike, can be reduced to a single, left-right dimension.

Does this make any sense? Why should views on (for example) gay marriage, taxation, and U.S. policy toward Iran have much of anything to do with one another? The answer is that it suits the Democratic Party and Republican Party’s mutual best interest to articulate clear and opposing positions on these issues and to present their platforms as being intellectually coherent. The two-party system can come under threat (as it potentially now is in the United Kingdom) when views on important issues cut across party lines.

Maybe that’s why we have so much trouble convincing people that there are libertarian voters.

Nate Silver looked at growing libertarian sentiment back in 2011.

Posted on April 14, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his book ‘The Libertarian Mind’ on WRMN’s The Dave & Dave Show

Posted on April 13, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cato Institute Policy Perspectives 2015

| 10:30 – 10:55 a.m. | Registration |

| 10:55 – 11:00 a.m. | Welcoming Remarks John Allison, Former President and CEO, Cato Institute |

| 11:00 – 11:30 a.m. | The Libertarian Mind in America David Boaz, Executive Vice President, Cato Institute |

| 11:30 a.m.– 12:10 p.m. | Power to the People Johan Norberg, Senior Fellow, Cato Institute |

Posted on April 10, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Is Rand Paul Arnie Vinick?

Rand Paul might take some inspiration from the final season of NBC’s late, lamented The West Wing. In that final 2005 season, presidential candidates battled to succeed President Jed Bartlet (Martin Sheen). The eventual nominees were Democratic Rep. Matthew Santos (Jimmy Smits) and Republican Sen. Arnold Vinick (Alan Alda).

Peter Funt, son and heir of Candid Camera creator Allen Funt, wrote in 2008 that the West Wing writers were in touch with Obama strategist David Axelrod as they created the Santos character, who was sort of a “test market” to “soften up millions of Americans for the task of electing the first minority president.” And he noted that Obama’s staffers “especially like the ending” of the West Wing plot, in which Santos narrowly defeats Vinick.

But Funt left out the part that might make Paul supporters optimistic. After the libertarianish Vinick got the Republican nomination, former Democratic strategist Bruno Giannelli (Ron Silver) went to him and told him that with his image he could win a landslide victory: You, he said, “are exactly where 60 percent of the voters are: Pro-choice, anti-partial birth, pro-death penalty, anti-tax, pro-environment and pro-business, pro-balanced budget.”Now, that’s not exactly Rand Paul’s policy portfolio. But Paul’s positions similarly cut across partisan divides and just might appeal to that same 60 percent majority.

But Funt left out the part that might make Paul supporters optimistic. After the libertarianish Vinick got the Republican nomination, former Democratic strategist Bruno Giannelli (Ron Silver) went to him and told him that with his image he could win a landslide victory: You, he said, “are exactly where 60 percent of the voters are: Pro-choice, anti-partial birth, pro-death penalty, anti-tax, pro-environment and pro-business, pro-balanced budget.”Now, that’s not exactly Rand Paul’s policy portfolio. But Paul’s positions similarly cut across partisan divides and just might appeal to that same 60 percent majority.

The high point of the West Wing campaign was a debate that broke the rules of both presidential debates and television drama: The “candidates” threw out the usual formal debate rules and just questioned each other, and the actors improvised their questions and answers on live television from a partially written script. They actually did two live performances that night, for the East Coast and the West Coast.

In the debate, Vinick showed those center-libertarian colors against Santos’s tired old big-government liberalism dressed up in appeals to hope. The morning after that debate aired on NBC, libertarian-leaning Republicans told each other, “if only a real candidate could articulate our values as well as a liberal actor did!”

Asked about creating jobs, Vinick declared, “Entrepreneurs create jobs. Business creates jobs. The President’s job is to get out of the way.”

On alternative energy:

I don’t trust politicians to choose the right new energy sources. I believe in the free market. You know, the government didn’t switch us from whale oil to the oil found under the ground. The market did that. And the government didn’t make the Prius the hottest selling car in Hollywood. That was the market that did that. In L.A. now, the coolest thing you can drive is a hybrid. Well, if that’s what the free market can do in the most car-crazed culture on Earth, then I trust the free market to solve our energy problems. You know, you know, the market can change the way we think. It can change what we want. Government can’t do that. That’s why the market has always been a better problem-solver than government and it always will be.

His closing statement:

Matt has more confidence in government than I do. I have more confidence in freedom — your freedom; your freedom to choose your child’s school, your freedom to choose the car or truck that’s right for you and your family, your freedom to spend or save your hard-earned money instead of having the government spend it for you. I’m not anti-government. I just don’t want any more government than we can afford. We don’t want government doing things it doesn’t know how to do or doing things the private sector does better or throwing more money at failed programs because that’s exactly what makes people lose faith in government.

And after the debate, a Zogby poll found that even among the young, liberal-skewing viewers of The West Wing, Vinick had crushed Santos. Before the episode, viewers between 18 and 29 preferred Santos over Vinick, 54 percent to 37 percent. But after the debate, Vinick led among viewers under age 30, 56 percent to 42 percent. Republicans can only dream of such numbers–unless maybe they try sounding like Arnie Vinick.

And after the debate, a Zogby poll found that even among the young, liberal-skewing viewers of The West Wing, Vinick had crushed Santos. Before the episode, viewers between 18 and 29 preferred Santos over Vinick, 54 percent to 37 percent. But after the debate, Vinick led among viewers under age 30, 56 percent to 42 percent. Republicans can only dream of such numbers–unless maybe they try sounding like Arnie Vinick.

West Wing producers were taken aback by the reactions of real live “voters” to their real live debate. After seven years of heroically portraying the honest, decent, liberal President Jed Bartlet–-an idealized Bill Clinton who wouldn’t take off his coat, much less his pants, in the Oval Office–-they weren’t about to let a crotchety old Republican beat their handsome Hispanic hero. So they conjured up a meltdown in a nuclear power plant that Vinick had supported, and Santos won the election.

If only the Republicans could nominate another Arnie Vinick, with strong convictions and appeal to independents–and there’s no nuclear meltdown–they might just find a majority in a presidential election.

Posted on April 10, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his book, The Libertarian Mind, at The Commonwealth Club of California

Posted on April 9, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Paul Krugman Can’t Find Any Libertarians

Paul Krugman has a blog post at the New York Times that seems to be based on no research at all. But it has a snappy four-cell matrix so you’ll know it’s like real economics.

Krugman’s argument is that “there basically aren’t any libertarians.” And here’s the graph that proves it:

See how small the letters are in two of the boxes? That shows you that there aren’t any people in those boxes. “There ought in principle, you might think, be people who are pro-gay-marriage and civil rights in general, but opposed to government retirement and health care programs — that is, libertarians — but there are actually very few.” And there are also very few people who are “socially illiberal” and supportive of government social programs, he says.

But you know, there’s research on this. David Kirby and I have done some of it, in studies on “the libertarian vote.” But two political scientists examined a similar matrix back in 1984 and found roughly even numbers of people in each box.

Part of the trick here is that Krugman has used a vague term, “socially liberal,” for one of the dimensions of the matrix, and a radical policy position, “no social insurance,” for the other dimension. The logical way would be to use either common vague terms for both dimensions – say “socially liberal/conservative” and “fiscally liberal/conservative” – or specific and similarly radical terms for both dimensions, something like “no social insurance” and “repeal all drug laws.” Wonder how many people would be in the boxes then?

“No social insurance” is a very radical position. Even many libertarians wouldn’t support it. Like Hayek. So to find the divisions in our society, we might choose a specific issue of personal freedom – gay marriage, say – along with an equally controversial economic policy such as school choice or a constitutional amendment to balance the budget.

If you use either set of dimensions, it’s pretty clear that you’re going to get substantial numbers of libertarians (broadly speaking) and also of those incongruous creatures Krugman can only call “hardhats.” Libertarians often call people who support substantial government intervention in both economic and personal issues “statists” or authoritarians. In our studies we call them populists, as does the Gallup Poll.

The media constantly discuss politics in terms of liberals and conservatives, so very few voters are even familiar with the term libertarian (or populist) and thus few choose it to describe themselves.

It is of course true that the number of “real” libertarians – people who read Hayek and Nozick and Rothbard, or Reason magazine, or indeed The Libertarian Mind – is small. Maybe a few hundred thousand? (Though Hayek was selling pretty well when the government created a financial collapse and responded by bailing out Wall Street.) Maybe a few million if you include Ayn Rand? But it’s also true that there aren’t many conservatives if you mean people have read The Conservative Mind, and not many liberals if you mean people who read John Rawls and Paul Starr.

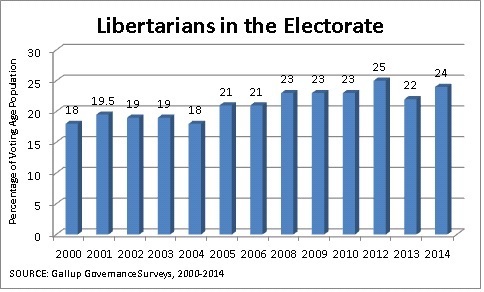

The question for politics, which is where Krugman started, is how many people there are who hold broadly libertarian views, or views that diverge from liberal and conservative approaches in a libertarian direction. That’s what pollsters try to measure. For more than 20 years now, the Gallup Poll has been using two questions to categorize respondents by ideology:

Some people think the government is trying to do too many things that should be left to individuals and businesses. Others think that government should do more to solve our country’s problems. Which comes closer to your own view?

Some people think the government should promote traditional values in our society. Others think the government should not favor any particular set of values. Which comes closer to your own view?

Here’s a graphic depiction of the number of respondents who gave libertarian answers to both questions in the Bush-Obama years:

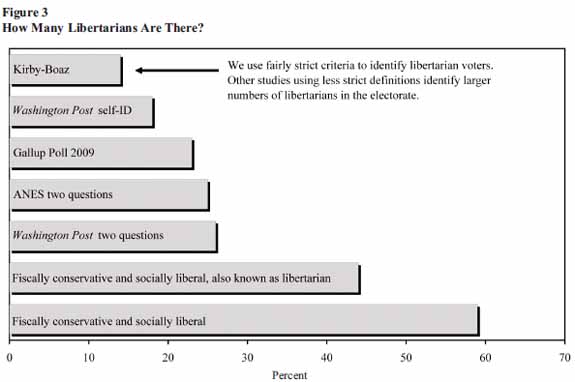

The Pew Research Center and the American National Election Studies also ask such questions, and in our studies on the libertarian vote we have drawn on all those data sets. By using narrower criteria than Gallup does, mostly by adding a third question, we found that 13 to 15 percent of Americans hold libertarian attitudes. In 2006 we commissioned Zogby International to ask our three ANES questions to 1,012 actual (reported) voters in the 2006 election. We asked half the sample, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal?” We asked the other half of the respondents, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal, also known as libertarian?”

The results surprised us. Fully 59 percent of the respondents said “yes” to the first question. That is, by 59 to 27 percent, poll respondents said they would describe themselves as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.”

The addition of the word “libertarian” clearly made the question more challenging. What surprised us was how small the drop-off was. A healthy 44 percent of respondents answered “yes” to that question, accepting a self-description as “libertarian.” We summed all that up in this handy but not necessarily helpful graph:

All these numbers are open to debate, of course. Do these views affect how people vote? I think our studies on the libertarian vote present evidence that they do. But I’m sorry that Paul Krugman didn’t do a Google search on “how many libertarians” before dashing off his post.

Krugman says there just aren’t many people who hold views that cross red/blue, liberal/conservative lines, who believe in, say, both gay marriage and lower taxes, or oppose both marijuana legalization and free trade. That is, there are no people who are, as he puts it, “socially liberal” but also “fiscally conservative.” In the real world, of course there are. It’s not hard to find them in polls, or by talking to people. Are they just inconsistent? Or might they have broadly libertarian views (or broadly pro-government views)?

If all this data doesn’t impress Krugman, maybe he’ll accept Radley Balko’s scientific analysis:

Libertarians are like dark matter. There may be no direct proof we exist, but you can infer us due to how we affect Alternet & Salon.

I don’t think a Princeton professor would give this paper a passing grade.

Posted on April 9, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses Rand Paul’s campaign on WNYC’s The Brian Lehrer Show

Posted on April 8, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his Newsweek op-ed on Rand Paul’s campaign on Sirius XM’s Stand Up! With Pete Dominick

Posted on April 8, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty