The Soul of America

David Boaz

President Biden launched his reelection campaign by declaring, “We’re in a battle for the soul of America. The question we’re facing is whether in the years ahead, we have more freedom or less freedom. More rights or fewer.” Music to libertarian ears. But one might question whether either party today is offering Americans more freedom, or truly understands the soul of America. The Founders gave us a mission statement for the United States of America, an expression of its soul:

lead

,

We hold these truths to be self‐evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

,

That mission statement created a legacy. The Pulitzer Prize‐winning historian Bernard Bailyn elaborated on how early Americans made those ideas real:

,

Written constitutions; the separation of powers; bills of rights; limitations on executives, on legislatures, and courts; restrictions on the right to coerce and wage war—all express the profound distrust of power that lies at the ideological heart of the American Revolution and that has remained with us as a permanent legacy ever after.

,

How are our leaders living up to those principles today? The idea of restricting power has too often been replaced by faith that a leader’s every passing thought should be turned into law, by legislation if possible, by executive order or administrative regulation if necessary. Worse, growing tribalism leads to an attitude that the point of gaining office is to use state power to reward “us” and to harm “them.”

President Biden correctly calls his predecessor’s attempt to overturn the election an assault on democracy and the Constitution. Too few Republican officials affirm that Biden won the election and that it was shockingly wrong to try to pressure election officials to “find” more votes. However, the president’s embrace of freedom seems to extend only to a few issues. He would raise taxes on both individuals and corporations, reducing our freedom to spend the money we earn; borrow and borrow (and borrow)—which crowds out private borrowing— and pile up debt, which is paid eventually with taxes or inflation. Government’s preferences are substituted for our own. Freedom to live as you want matters, too.

The costs of Biden’s regulations so far exceed those of Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama combined. Most of them restrict our freedom. Like his predecessor, Biden continues to impose costs on consumers through tariffs and other trade restrictions. His Federal Trade Commission seeks to break up America’s successful companies. Subsidies are handed to favored industries and firms. He would deny families the freedom to choose the best schools for their children.

Meanwhile, the two leading candidates for the Republican presidential nomination pound the table for freedom. Before his election loss, the former president’s great passions were to restrict international trade and immigration, and he threatened to send military troops into U.S. cities over the objections of local governments. Now he’s proposing military strikes in Mexico.

His chief Republican rival proclaims his support for free speech but has launched multiple legal assaults on the Walt Disney Co. after it issued a tepid criticism of a bill regulating what teachers could say about sexual orientation and gender identity. He barred Florida companies, including cruise ships, from setting their own vaccination policies. This is not your father’s idea of free enterprise. And all of this comes at a time when leading conservatives are writing things like “The right must be comfortable wielding the levers of state power,” and “using them to reward friends and punish enemies.”

Republican governors and legislatures are taking books out of schools—ranging from some that are actually problematic to biographies of Rosa Parks—and rushing to legislate restrictions on transgender people and “drag shows” without much careful consideration. It’s reminiscent of those who rushed in the early 2000s to ban same‐sex marriage. The current mania is partly in response to similarly rushed federal mandates regarding transgender policy on local governments.

In all this haste to legislate bans, mandates, taxes, regulations, subsidies, boondoggles, and punishments, who’s looking out for the soul of America?

Posted on June 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Continuing Effort to Deny that Libertarian‐ish Voters Exist

David Boaz

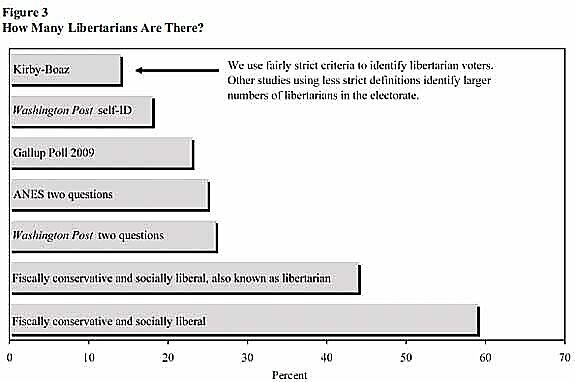

Here we go again. David Leonhardt of the New York Times dredges up a poorly designed chart from 2017 that purported to show that there are very few “fiscally conservative, socially liberal” American voters. At the time Karl Smith pointed out some basic design flaws in the analysis. Emily Ekins noted that determining the number of liberal, conservative, libertarian, and populist/communitarian/statist voters depends very much on the definitions you start with and the issues you choose. She concludes: “The overwhelming body of literature, however, using a variety of different methods and different definitions, suggests that libertarians comprise about 10–20% of the population, but may range from 7–22%.”

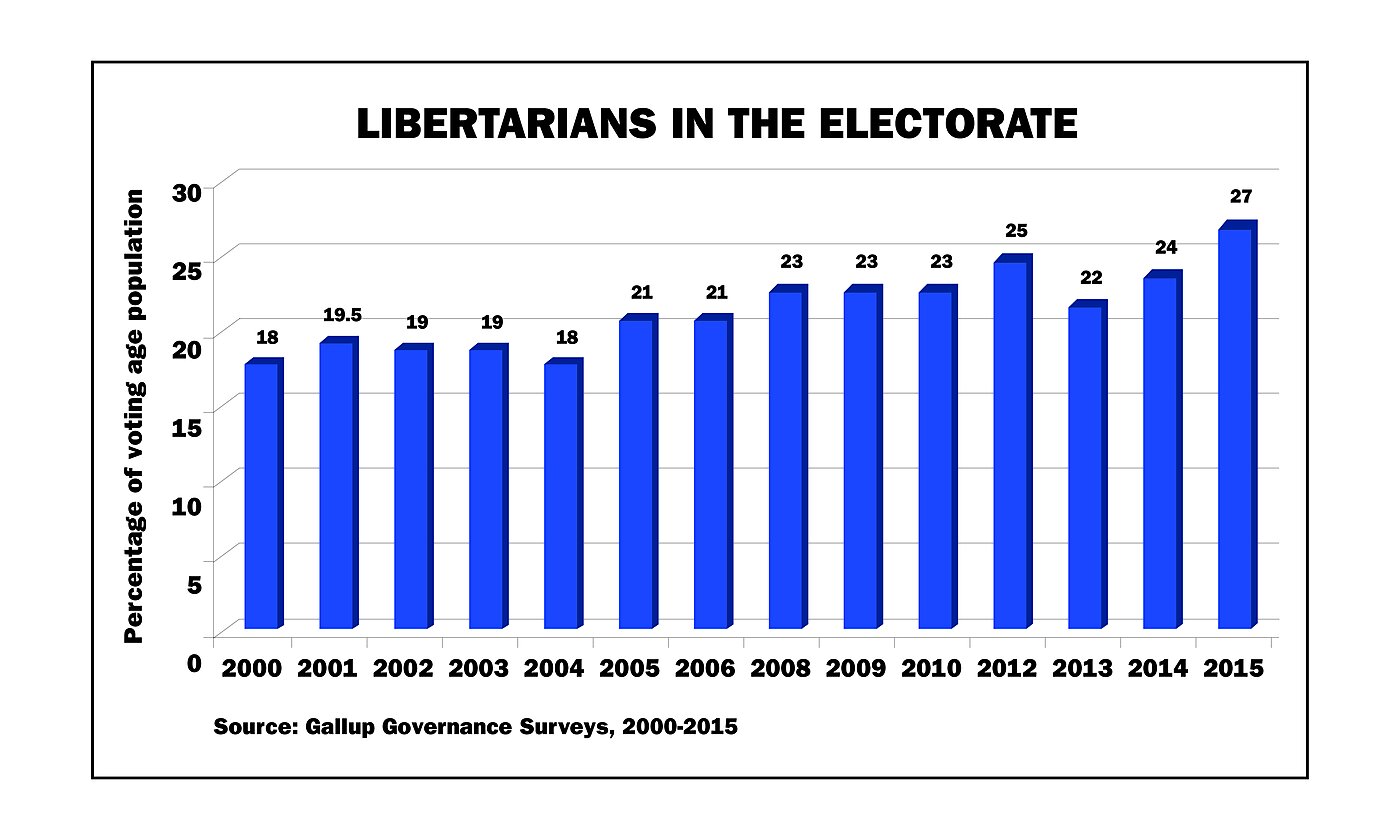

The Gallup Poll has regularly used a two‐question screen to divide voters into four ideological categories, and they typically found libertarians around the 20 percent mark.

Beginning in 2006 David Kirby and I used a three‐question screen to identify libertarians, and we found that with that stricter definition “libertarians” constituted about 13 percent of the population and 15 percent of reported voters. And note that if we insisted on agreement with the liberal or conservative position on all three questions, the number of liberals and conservatives would likely be quite a bit lower than 25 percent.

It’s quite possible, of course, that the Trump Effect on Republican voters, not to mention the anti‐Trump backlash among independent and Democratic voters would have significantly changed some of these pre‐Trump, “normal” findings.

We also commissioned Zogby International to ask our three American National Election Studies questions to 1,012 actual (reported) voters in the 2006 election. We asked half the sample, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal?” — the very categorization Leonhardt used in his column. We asked the other half of the respondents, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal, also known as libertarian?”

The results surprised us. Fully 59 percent of the respondents said “yes” to the first question. That is, by 59 to 27 percent, poll respondents said they would describe themselves as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.”

The addition of the word “libertarian” clearly made the question more challenging. What surprised us was how small the drop‐off was. A healthy 44 percent of respondents answered “yes” to that question, accepting a self‐description as “libertarian.” We summed all that up in this handy graph:

Leonhardt and others may well be right that there are more “socially conservative, fiscally liberal” voters than “fiscally conservative, socially liberal.” Though the latter are better educated, more affluent, and more likely to vote. And in any case the numbers are a lot closer than Leonhardt and his befuddled chart would have you believe. Also, much depends on the questions you ask. Kirby and I used broad philosophical questions, as did Gallup, Pew, and ANES. But you can also use specific issues, as did a Washington Post poll. The combination “abolish Medicare” and “repeal all drug laws” would find a huge percentage of SCFL voters and very few FCSL or libertarianish voters. “Gay people should be able to get married” plus “the government spends too much money” will get you a lot of FCSL voters. Which one is closer to actual American policy conflicts?

There’s plenty of room for debate about how to analyze the ideological positions of American voters. But looking at the available data is a good place to start.

Posted on May 30, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Jimmy Lai — Recipient of the 2023 Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty

Jimmy Lai, Cato Institute, Peter Goettler, Ian Vásquez, David Boaz, Lesley Albanese

Jimmy Lai has become a powerful symbol of the struggle for democratic rights and press freedom in Hong Kong as China’s Communist Party exerts ever greater control over the territory. In prison and denied bail, Lai is an outspoken critic of the Chinese government and advocate for democracy who faces charges that could keep him in jail for the rest of his life.

Posted on May 19, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Democracies, Autocracies, and Same‐Sex Unions

David Boaz

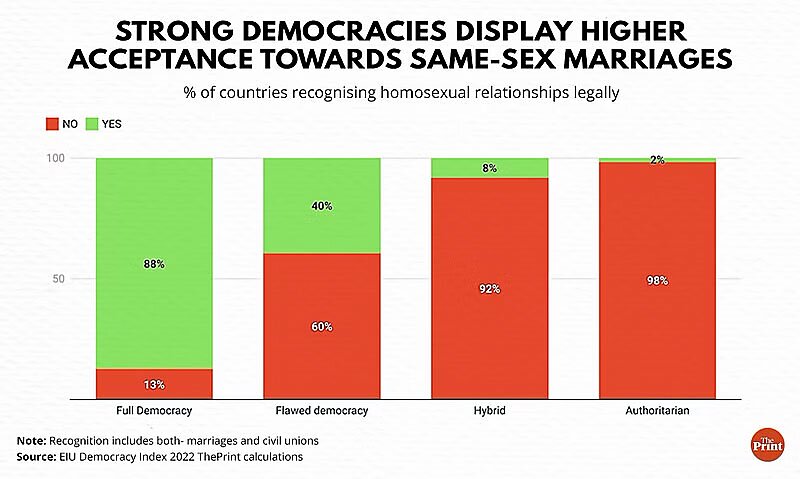

A new study by the Indian newspaper The Print, based on data from The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2022, finds that 88 percent of full democracies recognize same‐sex marriages or civil unions, while only 2 percent of authoritarian regimes do.

As my colleague Swaminathan Aiyar told the paper, “Autocracies do not recognise individual rights as fundamental and inalienable. Autocracies are organised on principles that allow the autocrat to discriminate on any grounds. In such countries, the progress of same‐sex rights will naturally be slower or non‐existent.” By contrast, implementation of same‐sex marriage in democratic countries proceeded very rapidly once it became a matter for debate. In 1989 Denmark became the first country in the world to legally recognize same‐sex unions, in the form of “registered partnerships.” In 2001 the first same‐sex marriage law came into effect, in the Netherlands.

In a sense this finding isn’t very surprising, of course: Liberal countries tend to be liberal. I’ve written about this before, citing a column written in 2013 by the British journalist Michael Hanlon. Hanlon wrote about a “morality gap” in the world that could be seen most clearly in attitudes toward gay rights. His column is worth quoting at length:

It is now clear, though not much talked about, that humanity, all 7.1 billion of us, tends to fall into one of two distinct camps. On the one side are those who buy into the whole post‐Enlightenment human rights revolution. For them the moral trajectory of the last 300 years is clear: once we were brutal savages; in a few decades, the whole planet will basically be Denmark, ruled by the shades of Mandela and Shami Chakrabarti.

And there’s some truth in this trajectory — except for the fact that it only applies to half the planet. The other half resolutely follows a different moral code: might is right, all men were not created equal and there is a right and a wrong form of sexual orientation.…

Let’s start with attitudes to gays, not because gay rights are the most important issue, but because attitudes to homosexuality show the morality gap in sharpest relief.…

A look at the timeline of gay rights shows a seemingly unstoppable barrage of permissiveness, with state after state passing laws first legalising homosexuality, then going further: permitting gay marriage and gay adoption and formalising gay relationships in terms of pensions and property rights. It’s tempting for those of us in this enlightened half of the world to think of this as a great wave of progress that rose up in the mid‐20th century and will sweep across the world.

Tempting, but wrong. In fact, in much of the world, received wisdom on homosexuality appears to be going into reverse.

Of course, this divide in the world is well known. It’s been discussed and analyzed in Pew Research studies, examined at HumanProgress.org, and included in the rankings of the Human Freedom Index. The findings from The Print show the divide in stark relief.

Liberalism is the most successful idea in the history of the world, yet it is now under attack in many parts of the world. Not just in countries such as Russia, China, Uganda, and India, but in liberal and democratic countries as well. Ideas we thought were dead are back. Socialism, protectionism, ethnic nationalism, antisemitism, even — for God’s sake — industrial policy. Liberals must sharpen their arguments and redouble their advocacy efforts on behalf of individual rights, free markets, limited government, and peace. Or as I like to say, we must continue to extend the promises of the Declaration of Independence — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — to places, and people, and aspects of life they have not yet reached.

Posted on May 3, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Lobbying Turns Green

David Boaz

I don’t mean to keep writing the same article about lobbying and special interests over and over. But the federal government keeps creating more and more opportunities for special interests to hire lobbyists. This week The Economist writes,

with up to $800bn in clean‐energy handouts now up for grabs over the coming decade, …

The energy industry as a whole spent nearly $300m last year on lobbying, the most since 2013 (see chart 1). Big oil and electric utilities, which had been reducing their spending on influence‐seeking before 2020, have ramped it up again; spending is growing in line with that of the biggest lobbyists, big pharma. Renewables firms went from spending an annual average of around $24m between 2013 and 2020, to $38m in 2021 and $47m in 2022. “We’ve now got an interesting new ecosystem of swamp creatures here,” says the government‐relations man at a giant renewable‐energy company.

And what caused this new ecosystem?

The reason is the passage last year of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The law funnels at least $369bn in direct subsidies and tax credits to decarbonisation‐related sectors (see chart 2). It came on the heels of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which also shovels billions in subsidies towards clean infrastructure. Some of the provisions offer generous tax credits, with no caps on the amount of spending eligible for the incentives. A mad investment rush, should it materialise, could lead to public expenditure of $800bn over the next decade. An official at a big utility says her firm has projects in the works across America that, if successful, will secure a staggering $2bn in funding from the two laws. “We stopped counting…we just have a big smile on our faces all the time these days,” confesses the renewables firm’s government‐relations man. “There is a lot there for a lot of people,” sums up a business‐chamber grandee. And, he adds, “A lot of lobbyists are interested in the spending.”

And as my colleague Scott Lincicome told Politico about another multi‐billion‐dollar pot of gold, the CHIPS and Science Act, “It would almost be corporate malpractice to not go after that cash.”

This is of course the standard story whenever Congress appropriates, or considers appropriating, a new pot of taxpayers’ money. The civics books explain that the people bring a problem to Congress, committees hold hearings and hear from expert witnesses, the issue is debated, Congress then maybe appropriates the money, and selfless experts in the bureaucracy spend it in the national interest. The reality is more like a feeding frenzy to get a piece of every new funding opportunity. It’s no surprise that that lobbying expenditures are reaching new highs in the spendthrift Biden administration.

Lobbying is protected by the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law … prohibiting … the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” But those who worry that corporate interests and the wealthy have too much influence in Washington should recognize the “supply‐side economics” of the problem: When government supplies billions — tens of billions — hundreds of billions of dollars to be handed out by appointed officials and the bureaucracy, you can bet that interested parties will leave no stone unturned in their effort to get a piece of that cash.

As Craig Holman of the Ralph Nader‐founded Public Citizen told Marketplace Radio during the 2009 financial crisis, “the amount spent on lobbying … is related entirely to how much the federal government intervenes in the private economy.”

Marketplace’s Ronni Radbill elaborated: “In other words, the more active the government, the more the private sector will spend to have its say…. With the White House injecting billions of dollars into the economy [in early 2009], lobbyists say interest groups are paying a lot more attention to Washington than they have in a very long time.”

Big government means big lobbying. When you lay out a picnic, you get ants. And today’s federal budget is the biggest picnic in history.

The Nobel laureate F. A. Hayek explained the process 80 years ago in his prophetic book The Road to Serfdom: “As the coercive power of the state will alone decide who is to have what, the only power worth having will be a share in the exercise of this directing power.”

That’s the worst aspect of the growth of lobbying: it indicates that decisions in the marketplace are being crowded out by decisions made by lobbyists and politicians, which means a more powerful government, less freedom, and less economic growth.

Posted on April 19, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cato Institute event, “Bruce Caldwell, Hayek; A Life,” aires on C‑SPAN 2

Posted on April 2, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Did Marx Make Lenin, or Did Lenin Make Marx?

David Boaz

Was Karl Marx one of the towering intellectual figures of the 19th century? It certainly seems that way. His work is widely assigned in college courses, far more than for instance John Locke and Adam Smith, much less F. A. Hayek or Ludwig von Mises.

But recently Phil Magness and Michael Makovi have advanced a different hypothesis: That Marx was a relatively minor figure in his own time, especially after the Marginal Revolution of the 1870s decisively refuted his economic analysis, and his reputation soared only after the Bolshevik Revolution — or the coup led by Vladimir Lenin — of 1917. See their academic paper here and a popular article here.

Recently I was looking at ideological bias in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, and I noticed that the book included 23 quotations from Marx. That’s the same as the combined total for John Locke and Adam Smith, the philosophical architects of our modern liberal world. (And far more than Hayek, Mises, Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand, or William F. Buckley Jr.)

But I wondered: how far back did Marx get such play in Bartlett’s, which has been published in 19 editions since 1855? What I found seems to add support to the thesis of Magness and Makovi. Marx (with Friedrich Engels) had 18 citations in the 1992 edition. That is, in Bartlett’s his relevance seems only to have risen since the collapse of the Soviet Union. But looking at previous editions, I see that Marx is not mentioned in the 1874 edition, published well after The Communist Manifesto, which so many college students are instructed to read. Nor in the 9th edition, after his death; this copy was published in 1905 but may have been edited by 1891. Not included in the 1919 (10th) edition, though his contemporary Herbert Spencer is well represented. Marx’s big break comes in the 11th edition, published in 1937 (though this copy was printed in 1942). In that edition Marx is represented with 17 quotations. (The 11th edition was edited by the journalist and novelist Christopher Morley, brother of the classical liberal journalist Felix Morley). There is no entry for either Locke or Smith. In the 1955 centennial edition, available through the Internet Archive, Marx again has 17 quotations. At last Locke and Smith get on the board, with 8 and 2 quotations respectively.

So what we know is this: Karl Marx begins publishing in the 1840s. He publishes his magnum opus, Capital, in 1867. He dies in 1883, but Engels keeps promoting and publishing his work. Through 1919 Marx goes unmentioned in the leading English‐language book of quotations. In the 1920s the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, using the vast resources of the Soviet state, embarks on a massive printing and distribution of Marx’s works in many languages. As the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm writes, “The cheap edition [of the Communist Manifesto] published in 1932 by the official publishing houses of the American and British Communist Parties in ‘hundreds of thousands’ of copies has been described as ‘probably the largest mass edition ever issued in English.’ ” And by 1937 Marx is well represented in Bartlett’s, while the most important theorists of Western liberalism are omitted. The efforts of Lenin and the Communist Party seem to have been the key factor in propelling Marx to the wide recognition we now take for granted.

Posted on March 28, 2023 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Cato Scholars on Vaccine Policies

David Boaz

The Cato Institute is committed to being a libertarian think tank: individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace. But one thing that’s often misunderstood is that Cato as such does not take institutional positions on particular policy questions. Cato scholars speak for themselves and have the freedom to reach their own conclusions, particularly on things that are contested among libertarians.

Recently there was an example of this as two Cato scholars appeared in major media to articulate their differing views on vaccines and how to apply libertarian principles in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of our senior fellows, Todd Zywicki, wrote in the Wall Street Journal on August 6 to explain why he is suing George Mason University, where he is a law professor, over their policy requiring COVID-19 vaccination. In particular, he objects to the application of the policy to people like him who have already had and recovered from COVID, and thus already have some degree of natural immunity.

Another Cato adjunct scholar, also a George Mason law professor, Ilya Somin, appeared on MSNBC on August 11 to discuss why he sees vaccine requirements as potentially justified and preferable to other policy options. Drawing on libertarian principles, he made the case that a disease like COVID involves the potential of harm to other people. Somin pointed out that mask mandates, lockdowns, and restrictions on international travel are all much more intrusive than the relatively slight imposition of a safe and effective vaccine. There is a particularly strong libertarian case that private institutions, and even the government when acting as employer, can set policies attached to what are voluntary relationships: employees, customers, students, and the like. Florida’s recent attempt to ban private businesses such as cruise lines from adopting vaccine requirements has already suffered defeat in court and is one example of an affront to libertarian sensibilities.

In this case as on other issues, we don’t require uniformity or suppress differing views among our scholars. And any one scholar’s individual view is not necessarily “Cato’s position” on a matter. That diversity of viewpoints and intellectual freedom is part of why Cato has been able to provide an effective voice for classical liberal and libertarian ideas across the entire range of public policy issues. The standards we uphold are for intellectual rigor and solid grounding in good data, especially for work Cato publishes. Our scholars also frequently write, publish, and engage in advocacy outside of Cato, which we happily encourage. It’s that reputation for intellectual honesty and serious engagement with opposing points of view which has helped put Cato routinely near the top of rankings of America’s most influential think tanks, making a difference for freedom in state capitals, on Capitol Hill, and at the Supreme Court, where Cato’s renowned amicus program is tied with the ACLU at the top of the rankings for filing on the winning side of major policy cases.

Posted on August 13, 2021 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Nixon Shock and the Libertarians

David Boaz

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon went on television and announced a three‐part New Economic Policy supposedly intended to stop inflation and increase economic growth. By executive order he would “close the gold window,” thus preventing foreign nations from exchanging U.S. dollars for U.S. gold; impose a 10 percent surcharge on imports; and order a freeze on wages and prices. Public reaction was good, and the Dow Jones Average rose the next day. The New York Times editorialized that “we unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved on all economic fronts.”

The few libertarians at the time had a different reaction. Milton Friedman wrote in his Newsweek column that the price controls “will end as all previous attempts to freeze prices and wages have ended, from the time of the Roman emperor Diocletian to the present, in utter failure.” Ayn Rand gave a lecture about the program titled “The Moratorium on Brains” and denounced it in her newsletter. Alan Reynolds, now a Cato senior fellow, wrote in National Review that wage and price controls were “tyranny … necessarily selective and discriminatory” and unworkable. Murray Rothbard declared in the New York Times that on August 15 “fascism came to America” and that the promise to control prices was “a fraud and a hoax” given that it was accompanied by a tariff increase.

Some libertarians who were gathered that night at the Denver home of David and Sue Nolan decided that Nixon’s announcement was the last straw: it was time to form a new political party. In meetings over the next 10 months they created the Libertarian Party and nominated a presidential ticket. One of the attendees at the first convention, in June 1972, was Ed Clark, a free‐market, antiwar lawyer who had decided to leave the Republican Party after Nixon’s speech. He soon became a member of the fledgling Libertarian Party and in 1980 became its most successful presidential candidate to that date.

Much has been said about the economic effects of the Nixon shock. Lew Lehrman wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2011, “The “Nixon Shock” was followed by a decade of one of the worst inflations of American history and the most stagnant economy since the Great Depression. The price of gold rose to $800 from $35. The purchasing power of a dollar saved in 1971 under Nixon has today fallen to 18 pennies. Nixon’s new economic policy sowed chaos for a decade.” There were intermittent gasoline shortages and lines until Ronald Reagan removed the price controls on oil. David Stockman told me in 1979, when I was new to the policy world, that closing the gold window had been the worst policy decision since he came to Washington. We’re still paying the price for the unleashing of inflation.

But I suppose there were a couple of positive outcomes from Nixon’s very bad decision: the creation of a stronger libertarian movement, and the fact that nobody has seriously proposed wage and price controls since.

Posted on August 13, 2021 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Is Orban Protecting Hungary from Libertarianism?

David Boaz

Tucker Carlson spent a week in Hungary extolling the accomplishments of Viktor Orban, the proud father of “illiberal democracy.” In an earlier edition of his show, Carlson had praised Orban for not “abandoning Hungary’s young people to the hard‐edged libertarianism of Soros and the Clinton Foundation.”

Absurd, right? George Soros and the Clinton Foundation libertarian, much less “hard‐edged” libertarians? Hardly.

And we might just have a laugh and leave it there. But maybe there’s a deeper sense in which Carlson has a point.

Libertarianism may be regarded as a political philosophy that applies the foundational ideas of liberalism consistently, following liberal arguments to conclusions that would limit the role of government more strictly and protect individual freedom more fully than other classical liberals would. But modern liberals such as Soros and Bill Clinton share a lot of those basic ideas with libertarians.

As Fareed Zakaria wrote about the success of libertarians,

They are heirs to a tradition that has changed the world. Consider what classical liberalism stood for in the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was against the power of the church and for the power of the market; it was against the privileges of kings and aristocracies and for dignity of the middle class; it was against a society dominated by status and land and in favor of one based on markets and merit; it was opposed to religion and custom and in favor of science and secularism; it was for national self‐determination and against empires; it was for freedom of speech and against censorship; it was for free trade and against mercantilism. Above all, it was for the rights of the individual and against the power of the church and the state.

In all those ways libertarians and other liberals changed the Western world and increasingly the entire world. Today libertarians, liberals such as Soros and Clinton, and conservatives such as Mitt Romney and Boris Johnson agree on such basic liberal principles as private property, markets, free trade, the rule of law, government by consent of the governed, constitutionalism, free speech, free press, religious freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, peace, and a generally free and open society. Not without plenty of arguments, of course, over the scope of government and the rights of individuals, from taxes and the welfare state to drug prohibition and war. But as Brian Doherty wrote in Radicals for Capitalism, his history of the libertarian movement, we live in a liberal world that “runs on approximately libertarian principles, with a general belief in property rights and the benefits of liberty.”

So one might say that with all the differences libertarians have with Soros—who has been the target of anti‐Semitic campaigning by Orban—or with the Clinton Foundation, they are at least more liberal than Orban’s “illiberal state” modeled on the successes of Russia, China, and Turkey, a regime that is shutting down universities, taking over media, suspending parliament, chipping away at democracy, and undermining the rule of law.

And in that sense, while Soros and the Clinton Foundation are hardly libertarian, much less “hard‐edged” libertarians, their conflict with the Orban regime does involve issues fundamental to the conflict between libertarianism and authoritarianism.

Posted on August 11, 2021 Posted to Cato@Liberty