How to Get a Piece of the Taxpayers’ Money

Two articles in the same section of the Washington Post remind us of how government actually works. First, on page B1 we learn that it pays to know the mayor:

D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser has pitched her plan to create family homeless shelters in almost every ward of the city as an equitable way for the community to share the burden of caring for the neediest residents.

But records show that most of the private properties proposed as shelter sites are owned or at least partly controlled by major donors to the mayor. And experts have calculated that the city leases would increase the assessed value of those properties by as much as 10 times for that small group of landowners and developers.

Then on B5 an obituary for Martin O. Sabo, who was chairman of the House Budget Committee and a high-ranking member of the Appropriations Committee, reminds us of how federal tax dollars get allocated:

Politicians praised Mr. Sabo, a Norwegian Lutheran, for his understated manner and ability to deliver millions of dollars to the Twin Cities for road and housing projects, including the Hiawatha Avenue light-rail line and the Minneapolis Veterans Medical Center.

Gov. Mark Dayton (D) said Minnesota has important infrastructure projects because of Mr. Sabo’s senior position on the House Appropriations Committee.

We all know the civics book story of how laws get made. Congress itself explains the process to young people in slightly less catchy language than Schoolhouse Rock:

Laws begin as ideas. These ideas may come from a Representative—or from a citizen like you. Citizens who have ideas for laws can contact their Representatives to discuss their ideas. If the Representatives agree, they research the ideas and write them into bills….When the bill reaches committee, the committee members—groups of Representatives who are experts on topics such as agriculture, education, or international relations—review, research, and revise the bill before voting on whether or not to send the bill back to the House floor.

If the committee members would like more information before deciding if the bill should be sent to the House floor, the bill is sent to a subcommittee. While in subcommittee, the bill is closely examined and expert opinions are gathered before it is sent back to the committee for approval.

When the committee has approved a bill, it is sent—or reported—to the House floor. Once reported, a bill is ready to be debated by the U.S. House of Representatives.

Ah yes … an idea, from a citizen, which is then researched, and studied by experts, and debated by representatives, and closely examined and carefully considered. But it does help if you know the mayor, or if your representative has enough clout to slip goodies for his constituents into a bill – often without being researched, and studied by experts, and closely examined, and debated.

I wrote about this in The Libertarian Mind, in a chapter titled “What Big Government Is All About” – not the civics book version, but the way laws actually get made and money actually gets spent.

Posted on April 1, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

President Obama and “President” Castro

News reports about President Obama’s visit to Cuba are regularly referring to his meeting with “Cuban President Raul Castro.” But Castro is not a president in the same sense that President Obama is. He’s not even a president in the dictionary sense. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “president” as “the elected head of a republican state.” Raul Castro was not elected, and Cuba is not a republic. Castro is a military dictator. That may not be a polite thing to say, but journalists are supposed to tell the truth, not worry about the feelings of the powerful. Indeed, according to the distinguished journalists Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, in their book The Elements of Journalism, written under the auspices of the Nieman Foundation, journalism’s first obligation is to tell the truth. The truth is that Raul Castro is, as Fidel Castro was, a dictator who rules with the support of the military.

Even the Wall Street Journal refers to “Cuban President Raul Castro.” I particularly regret this, because back in 2006 I called them out for their double standard on dictators, in a letter they published. They had written in an obituary note:

Gen. Alfredo Stroessner, the military strongman who ruled Paraguay from 1954 until 1989. Among 20th century Latin American leaders, only Cuban President Fidel Castro has served longer.

Why, I asked,

do you describe Gen. Alfredo Stroessner as a “military strongman” and Fidel Castro as “Cuban president” (“A Flair for Flavor,” Aug. 19)? Both came to power through bullets, not ballots, and ruled with an iron hand. Mr. Stroessner actually held elections every five years, sometimes with opposition candidates, though of course there was no doubt of the outcome. Mr. Castro dispensed with even the pretense of elections. Both ruled with the support of the army. In Cuba’s case, the armed forces were headed by Mr. Castro’s brother. So why does the Journal not give Stroessner his formal title of “president,” and why does it not describe Castro accurately as a “military strongman?”

One could make the same point about Chile’s Augusto Pinochet. He was formally the president, but newspapers generally referred to him as a military dictator. Pinochet ruled with an iron hand for 17 years. After 15 years he held a referendum on his rule. When he lost, he held elections and stepped down from power. That’s more than the Castro brothers have done after 57 years.

Posted on March 21, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Reagan’s Russia Trip Should Be Obama’s Roadmap in Cuba

When staunchly anti-communist Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980 — in the 64th year of Communist Party rule in Russia — no one expected that only eight years later he would end his second term by making a friendly visit to Moscow.

But he did, and what he did there should guide President Obama as he prepares to visit to Cuba — the first visit by a sitting president since Fidel Castro’s communist revolution in 1959 — on steps the president can take to usher in true freedom for the Cuban people.

There’s a difference, of course: In 1980, the Soviet Union and the United States had thousands of nuclear weapons aimed at one another, and Americans feared a clash between superpowers. Reagan’s main mission was to prevent those weapons from being used. We don’t face such high stakes with Cuba, but Americans do believe that people everywhere deserve to be free, and that’s a message worth presenting wherever people lack freedom.

Reagan went to Moscow to negotiate an arms control agreement with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. He could have left it at that — few Americans would have noted an absence of ideological speechmaking during a diplomatic visit. But since his televised 1964 “A Time for Choosing” address on behalf of the GOP presidential nominee, Sen. Barry Goldwater, and before, Reagan had been an evangelist for human rights and economic freedom as universal values, and he didn’t want to pass up the singular opportunity to talk about those values behind the Iron Curtain. He made the decision to strengthen Soviet dissidents and vigorously advocate for the American system of free enterprise and limited government against longstanding Soviet misrepresentations.

He stopped in Finland on his way to the USSR and told a crowd in Helsinki, “There is no true international security without respect for human rights. … The greatest creative and moral force in this new world, the greatest hope for survival and success, for peace and happiness, is human freedom.”

He asked “why Soviet citizens who wish to exercise their right to emigrate should be subject to artificial quotas and arbitrary rulings. And what are we to think of the continued suppression of those who wish to practice their religious beliefs?” Obama should ask the same in Cuba.

In Moscow, Reagan met with almost 100 dissidents — “human rights activists and Jewish refuseniks, veterans of labor camps and Siberian exile and the wives and children of some still imprisoned,” according to the Los Angeles Times. He told them: “I came here to give you strength, but it is you who have strengthened me. While we press for human lives through diplomatic channels, you press with your very lives, day in and day out, year after year, risking your homes, your jobs and your all.” He reminded them “it is the individual who is always the source of economic creativity.”

Obama likewise plans to meet with Cuban dissidents, and he should seek to give them similar hope.

[pullquote]A few years after Reagan went to Moscow, the Soviet Union was history. Cubans would revere Obama if the Castro regime has a similar end.[/pullquote]Reagan also gave a celebrated address at Moscow State University, one that compares to Obama’s speech to Chinese college students in 2009. Both presidents, both great communicators, outlined values and goals that are not just American but are, or should be, universal. But there were some clear differences in the philosophies they presented.

President Obama eloquently defended freedom in an authoritarian country: “We also don’t believe that the principles that we stand for are unique to our nation. These freedoms of expression and worship — of access to information and political participation — we believe are universal rights.” But he missed the opportunity to emphasize the importance of freedom of enterprise, property rights and limited government as American values. Those are not only the conditions that create growth and prosperity, they are the necessary foundation for personal and political liberty.

Contrast Obama’s remarks with Reagan’s to Soviet students in 1988. Reagan extolled the values of democracy and openness, and he noted that American democracy is not a plebiscitary system but a way to ensure that the governors don’t exceed the consent of the governed: “Democracy is less a system of government than it is a system to keep government limited, unintrusive; a system of constraints on power to keep politics and government secondary to the important things in life, the true sources of value found only in family and faith.”

He tied all of these freedoms to the American commitment to economic freedom as well. Throughout the speech he tried to enlighten students, who had grown up in a communist system, about the meaning of free enterprise:

“Some people, even in my own country, look at the riot of experiment that is the free market and see only waste. What of all the entrepreneurs that fail? Well, many do, particularly the successful ones; often several times. And if you ask them the secret of their success, they’ll tell you it’s all that they learned in their struggles along the way; yes, it’s what they learned from failing. … And that’s why it’s so hard for government planners, no matter how sophisticated, to ever substitute for millions of individuals working night and day to make their dreams come true. The fact is, bureaucracies are a problem around the world.”

President Obama said some important things to the Chinese students. But his failure to note the centrality of economic freedom in the American experiment — which he also omitted in a commencement address the year before — could easily lead listeners to conclude that he cares little for economic liberty. He has a chance to dismiss that concern when he speaks to Cubans next week.

Obama might argue that China had already moved toward capitalism by the time of his visit, so it made sense that he focused on civil and political liberties. That’s not the case in Cuba, which keeps proclaiming baby steps to opening markets without much actual evidence. There, the president needs to speak directly to Cubans about human rights, political freedom, freedom of expression and the market freedoms that sustain those liberties and bring prosperity. Cuba doesn’t need a central plan for capitalism, it just needs to start lifting the restrictions on normal economic activity.

The president should take Reagan’s approach, even if it doesn’t pay immediate dividends. Cuba’s change will be gradual. But that fact doesn’t change the necessity — it makes it more imperative — for the leader of the free world to offer Cubans a way forward.

A year after Reagan’s Moscow visit and, more importantly, four years after the reformist Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union, peaceful revolutions in Eastern Europe ended Soviet control. Two years after that, the Soviet Union itself was dissolved. We don’t know how long Cuba’s transformation from autocratic state socialism to free-market democracy will take. But the Cuban people would revere Obama if the Castro regime saw a similar dissolution, and if the president’s words helped to inspire that transformation.

Posted on March 18, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Was the “Libertarian Moment” Wishful Thinking? A Debate

Less than 18 months ago, a cover story for the New York Times Magazine asked, “Has the ‘libertarian moment’ finally arrived?” From public suspicion of the surveillance state, to increasing tolerance for marijuana legalization, to marriage equality, to weariness with war—the article argued that after years of intellectual work, “for perhaps the first time,” libertarianism has “genuine political momentum on its side.” However, the Rand Paul presidential campaign failed to catch fire. The two breakout candidates of the presidential campaign have been a socialist and an authoritarian. The idea of tolerance seems increasingly quaint, as Mexicans and Muslims have become the target of public frustrations. And the public seems to have forgotten its weariness with war, as the Islamic State continues its brutal terrorism. Was all this talk of the libertarian moment simply wishful thinking? Or was the libertarian moment never about politics in the first place? Join David Boaz, Matt Welch, Ramesh Ponnuru, and Conor Friedersdorf for a wide-ranging conversation on the future of libertarianism.

Posted on March 16, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz participates in the event “Carrots, Sticks and Nudges: Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom” hosted by the Milken Institute

Posted on March 5, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses Donald Trump’s presidential campaign on Sinclair Broadcast Group

Posted on March 2, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses conservatism in election 2016 on Al Jazeera America’s The Third Rail

Posted on February 21, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

A Reading List for Presidents’ Day

As government workers – though only about a third of private-sector office workers – get a day off for Presidents’ Day (legally, though not in fact, George Washington’s Birthday), I thought I’d offer some reading about presidents.

First, my own tribute to our first president, the man who led America in war and peace and who gave up power to make us a republic:

Give the last word to Washington’s great adversary, King George III. The king asked his American painter, Benjamin West, what Washington would do after winning independence. West replied, “They say he will return to his farm.”

“If he does that,” the incredulous monarch said, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

Then, of course, Gene Healy’s book The Cult of the Presidency, which argues that 200 years after Washington, “presidential candidates talk as if they’re running for a job that’s a combination of guardian angel, shaman, and supreme warlord of the earth.” Buy it today, at a 50 percent discount!

Gene updated that argument with a short ebook, False Idol: Barack Obama and the Continuing Cult of the Presidency. As they say, start reading in minutes!

And then you can read my short response to Politico’s question, who were the best and worst presidents? I noted:

Presidential scholars love presidents who expand the size, scope and power of government. Thus they put the Roosevelts at the top of the list. And they rate Woodrow Wilson – the anti-Madisonian president who gave us the entirely unnecessary World War I, which led to communism, National Socialism, World War II, and the Cold War –8th. Now there’s a record for President Obama to aspire to! Create a century of war and terrorism, and you can move up from 15th to 8th.

Hmmm, maybe it would be better to just read a biography of George Washington.

Posted on February 15, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Why We Celebrate Washington’s Birthday

Monday, February 22, will be the anniversary of George Washington’s birth, although the federal government in typical federal government fashion has instructed us to observe Washington’s Birthday (not Presidents’ Day) on a convenient Monday sometime before the actual date. There’s a reason that we should celebrate George Washington rather than a panoply of presidents.

I wrote this several years ago:

George Washington was the man who established the American republic. He led the revolutionary army against the British Empire, he served as the first president, and most importantly he stepped down from power.

In an era of brilliant men, Washington was not the deepest thinker. He never wrote a book or even a long essay, unlike George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams. But Washington made the ideas of the American founding real. He incarnated liberal and republican ideas in his own person, and he gave them effect through the Revolution, the Constitution, his successful presidency, and his departure from office.

What’s so great about leaving office? Surely it matters more what a president does in office. But think about other great military commanders and revolutionary leaders before and after Washington—Caesar, Cromwell, Napoleon, Lenin. They all seized the power they had won and held it until death or military defeat.

John Adams said, “He was the best actor of presidency we have ever had.” Indeed, Washington was a person very conscious of his reputation, who worked all his life to develop his character and his image.

In our own time Joshua Micah Marshall writes of America’s first president, “It was all a put-on, an act.” Marshall missed the point. Washington understood that character is something you develop. He learned from Aristotle that good conduct arises from habits that in turn can only be acquired by repeated action and correction – “We are what we repeatedly do.” Indeed, the word “ethics” comes from the Greek word for “habit.” We say something is “second nature” because it’s not actually natural; it’s a habit we’ve developed. From reading the Greek philosophers and the Roman statesmen, Washington developed an understanding of character, in particular the character appropriate to a gentleman in a republic of free citizens.

What values did Washington’s character express? He was a farmer, a businessman, an enthusiast for commerce. As a man of the Enlightenment, he was deeply interested in scientific farming. His letters on running Mount Vernon are longer than letters on running the government. (Of course, in 1795 more people worked at Mount Vernon than in the entire executive branch of the federal government.)

He was also a liberal and tolerant man. In a famous letter to the Jewish congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, he hailed the “liberal policy” of the United States on religious freedom as worthy of emulation by other countries. He explained, “It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.”

And most notably, he held “republican” values – that is, he believed in a republic of free citizens, with a government based on consent and established to protect the rights of life, liberty, and property.

From his republican values Washington derived his abhorrence of kingship, even for himself. The writer Garry Wills called him “a virtuoso of resignations.” He gave up power not once but twice – at the end of the revolutionary war, when he resigned his military commission and returned to Mount Vernon, and again at the end of his second term as president, when he refused entreaties to seek a third term. In doing so, he set a standard for American presidents that lasted until the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose taste for power was stronger than the 150 years of precedent set by Washington.

Give the last word to Washington’s great adversary, King George III. The king asked his American painter, Benjamin West, what Washington would do after winning independence. West replied, “They say he will return to his farm.”

“If he does that,” the incredulous monarch said, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

I talked about George Washington in this Cato Daily Podcast in 2007.

Posted on February 12, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty

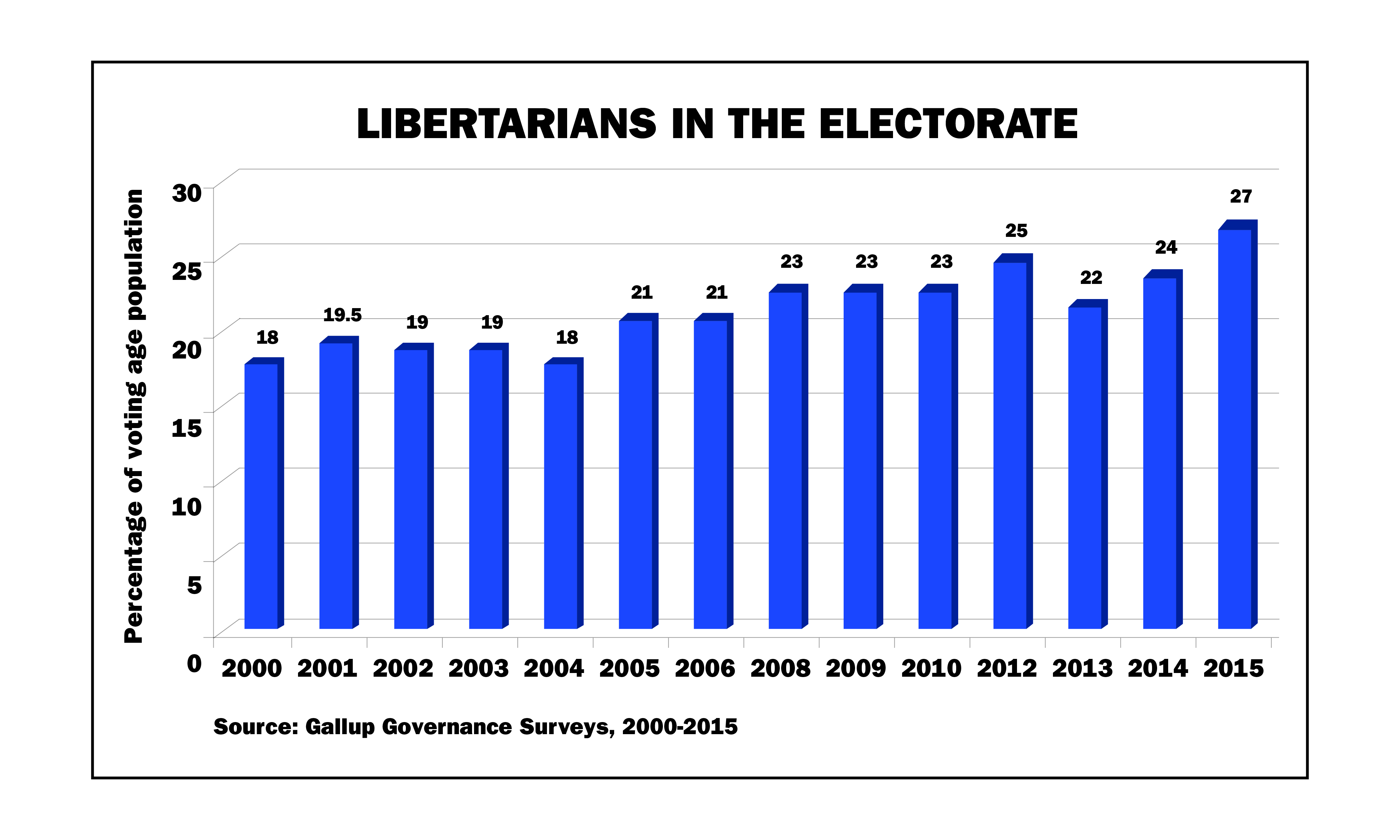

Gallup Finds More Libertarians in the Electorate

The Gallup Poll has a new estimate of the number of libertarians in the American electorate. In their 2015 Governance survey they find that 27 percent of respondents can be characterized as libertarians, the highest number it has ever found. The latest results also make libertarians the largest group in the electorate, as compared to 26 percent conservative, 23 percent liberal, and 15 percent populist.

For more than a dozen years now, the Gallup Poll has been using two questions to categorize respondents by ideology:

- Some people think the government is trying to do too many things that should be left to individuals and businesses. Others think that government should do more to solve our country’s problems. Which comes closer to your own view?

- Some people think the government should promote traditional values in our society. Others think the government should not favor any particular set of values. Which comes closer to your own view?

Combining the responses to those two questions, Gallup found the ideological breakdown of the public shown below. With these two broad questions, Gallup consistently finds about 20 percent of respondents to be libertarian, and the number has been rising .

.

Two years ago David Kirby found that libertarians made up an even larger portion of the Republican party.

So why isn’t all this supposed libertarian sentiment being reflected in candidates and elections? There have been plenty of analyses in the past week, including my own, about why Rand Paul didn’t attract this potentially large bloc of libertarian voters. Maybe people don’t see issues as equally salient; some libertarians may wish that Republicans weren’t so socially reactionary, but still vote Republican on the basis of economic issues. Some, as Lionel Shriver writes in the New York Times, feel “forced to vote Democratic because the Republican social agenda is retrograde, if not lunatic — at the cost of unwillingly endorsing cumbersome high-tax solutions to this country’s problems.”

For now I just want to note that there are indeed a lot of voters who don’t fit neatly into the red and blue boxes. The word “libertarian” isn’t well known, so pollsters don’t find many people claiming to be libertarian. And usually they don’t ask. But a large portion of Americans hold generally libertarian views – views that might be described as fiscally conservative and socially liberal.

David Brooks wrote recently that the swing voters in 2016 will be people who don’t think big government is the path to economic growth and don’t know why a presidential candidate would open his campaign at Jerry Falwell’s university. Those are the voters who push American politics in a libertarian direction. David Bier and Daniel Bier wrote last summer about how many policy issues show a libertarian trend over the past 30 years. Find a colorful chart illustrating their findings here.

Politics is often frustrating for libertarians, never more so than during this presidential election when the leading presidential candidates seem to be a protectionist nationalist with a penchant for insult, a self-proclaimed socialist, and a woman who proudly calls herself a “government junkie.” But polls show libertarian instincts in the electorate, just waiting for candidates who can speak to them.

Read more about the libertarian vote in our original study or in our 2012 ebook.

Posted on February 10, 2016 Posted to Cato@Liberty