Minimum Wage Hikes in Theory and Reality

Don Boudreaux recently despaired that only 26 percent of economists surveyed agreed that

If the federal minimum wage is raised gradually to $15-per-hour by 2020, the employment rate for low-wage US workers will be substantially lower than it would be under the status quo.

In the University of Chicago Booth School of Business’s regular survey of distinguished policy economists chosen for ideological diversity, 24 percent disagreed with the statement, and 38 percent said they were uncertain.

Some said that employment effects were likely, but they might not be “substantial.” That’s an empirical question, of course, and knowing the direction of a change doesn’t necessarily tell us its magnitude. In addition, each person’s definition of “substantial” might be different. Boudreaux doesn’t think there should be much uncertainty:

Would 74 percent of my fellow economists either disagree that, be “uncertain” that, or have no opinion on the question of whether a forced 107 percent increase in the price of the likes of 737, 777, and 787 jetliners would cause airlines to cut back substantially on the number of new jetliners they buy from Boeing? Or what if the question were about the prices of fast-food? Would 74 percent of these economists either disagree that, be “uncertain” that, or have no opinion on the question of whether a forced 107 percent increase in the prices of the likes of Big Macs, Baconators, and buckets of KFC fried chicken would cause consumers to cut back substantially on the amount of food they purchase at fast-food restaurants?

But who am I to jump into this battle of economists? Just a lowly newspaper reader, that’s all. And as it happens, Boudreaux posted his critique on Sunday, and on Monday I read an interview in the Wall Street Journal with Sally Smith, CEO of Buffalo Wild Wings. She runs a chain of more than 1,000 sports bars, and she’s trying to expand. Here’s part of her interview:

WSJ: How are minimum-wage increases affecting the way you make business decisions?

MS. SMITH: You look at where you can afford to open restaurants. We have one restaurant in Seattle, and we probably won’t be expanding there. That’s true of San Francisco and Los Angeles, too. One of the unintended consequences of rising minimum wages is youth unemployment. Almost 40% of our team members are under age 21. When you start paying $15 an hour, are you going to take a chance on a 17-year-old who’s never had a job before when you can find someone with more experience?

WSJ: Are you turning to automation to reduce labor costs?

MS. SMITH: We are testing server hand-held devices for order-taking in 30 restaurants now, and we’ll roll them out to another 30 in the next month and another 30 by the end of the year. Servers like it because they can take on more tables and earn more tips. Eventually we’ll have tablets where guests can place their own order from the table and pay for it.

Ms. Smith is no economist. (She has a BSBA in accounting and finance, and served as CFO of Buffalo Wild Wings and other companies for about 10 years before becoming CEO in 1996.) She’s just a CEO trying to make revenues come out ahead of costs. And when she thinks about a substantial increase in the minimum wage, her thoughts turn to not expanding, hiring more experienced workers, and using technology so fewer servers can serve more customers.

She doesn’t seem as uncertain about the effects on employment as the academic economists do.

Posted on October 27, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

How Bernie Sanders Is Like Ron Paul

How Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul are alike:

- Both ran for president in their 70s, without any encouragement from pundits, politicians, or political operatives.

- Both were far more interested in talking about ideas and policies than in criticizing their opponents. (Though I don’t recall Paul taking valuable debate time to defend his chief opponent on her most vulnerable point. Sanders not only drew applause for saying there was no point in talking about Hillary Clinton’s private email server, he raised more than a million dollars during the debate by sending out an email with video of his grant of absolution.)

- Both Ron Paul and Bernie Sanders exploded on the internet during an early debate. Google searches for Ron Paul shot up when he and Rudy Giuliani had a heated confrontation over the causes of the 9/11 attacks in the May 15, 2007, Republican debate. Sanders gained three times as many Twitter followers as Clinton during last night’s debate.

- Each was the most noninterventionist and least prohibitionist candidate on their respective stages – though that’s a low bar. Sanders sounded pretty noninterventionist, but then continued: “When our country is threatened, or when our allies are threatened, I believe that we need coalitions to come together to address the major crises of this country. I do not support the United States getting involved in unilateral action.” The United States has alliances across the world, so that’s a fairly open-ended commitment. And imprudent intervention is not made much more prudent by having a coalition.

How Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul are different:

- Capitalism vs. socialism.

Posted on October 14, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

The Divide between Pro-Market and Pro-Business

For the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Tea Party is no picnic. And the long conflict between pro-market and pro-business forces may lead to some divisive Republican primaries next year.

Years ago I helped to create an organization for business people who opposed crony capitalism and other forms of government help for business. We considered the clear and blunt name Business Leaders Against Subsidies and Tariffs, or BLAST, but eventually we settled on the more elegant Council for a Competitive Economy.

After we launched in 1979, our first big project was opposing the bailout of the Chrysler Corp. At the time, Chrysler was the 10th-largest industrial corporation in the United States, and a $1.5 billion federal loan guarantee for a private corporation was front-page news. Chrysler, the United Auto Workers and big lobbying firms swarmed Capitol Hill in a full-court press.

“Crony capitalists who seek government aid have no cause for decrying government rules.”

The Council for a Competitive Economy took out full-page ads declaring, “Bailing out Chrysler with taxpayers’ money would be a big mistake. Such a bailout would be another giant step away from a free, competitive economy.” With the Chamber of Commerce taking no position on a proposed government subsidy for a single private company, we were almost alone in vigorously defending the free market.

We lost that battle, of course, and the Chrysler Corp. lived to request more bailouts in later years.

A few months after that battle, the automobile companies started agitating for restrictions on Japanese imports. Again, the Council sprang into action. Board member Joe Coberly, a well-known Los Angeles Ford dealer, told a House committee that “the effort to impose restrictions on foreign cars is a conspiracy to thwart the American consumer.”

I delve into this history to point out that the conflict between free markets and cronyism has been going on for decades.

In June 2009 the chamber launched a $100 million “Campaign for Free Enterprise.” Chamber president Thomas Donohue told The Wall Street Journal that an “avalanche of new rules, restrictions, mandates and taxes” could “seriously undermine the wealth and job-creating capacity of the nation.”

The chamber was just a few months late with its campaign to save economic freedom. In late 2008 the chamber strongly backed the Wall Street bailout. After the House of Representatives initially rejected the Troubled Asset Relief Program, the chamber sent a blunt message to House Republicans: “Make no mistake: When the aftermath of congressional inaction becomes clear, Americans will not tolerate those who stood by and let the calamity happen.”

In early 2009 the chamber endorsed President Obama’s $787 billion stimulus bill. While free-marketers denounced the bill as “Porkulus,” and a Tea Party movement grew up in opposition to it, Mr. Donohue said, “With the markets functioning so poorly, the government is the only game in town capable of jump-starting the economy.”

In 2014 big business opposed several of the most free-market members of Congress, and even a Ron Paul-aligned Georgia legislator who opposed taxpayer funding for the Atlanta Braves.

The U.S. chamber jumped into a Republican primary in Grand Rapids, Mich., to try to take down Rep. Justin Amash, probably the most pro-free-enterprise and most libertarian member of Congress. Free-market groups, including the Club for Growth, Freedomworks and Americans for Prosperity, strongly backed Mr. Amash.

And now the chamber plans to spend up to $100 million on the 2016 campaign. Roll Call, a Capitol Hill newspaper, reports, “Some of business’ top targets in 2016 will be right-wing, tea party candidates, the types that have bucked the corporate agenda in Congress by supporting government shutdowns, opposing an immigration overhaul and attempting to close the Export-Import Bank.” Politico adds a highway bill to big business’ list of grievances against fiscal conservatives.

This clash between pro-market and pro-business is an old one. Adam Smith wrote “The Wealth of Nations” to denounce mercantilism, the crony capitalism of his day. Milton Friedman said at a 1998 conference: “There’s a common misconception that people who are in favor of a free market are also in favor of everything that big business does. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

That long-ago ad opposing the first Chrysler bailout warned businesses that government money always comes with strings attached. You can’t support subsidies for exports, protection from imports, bailouts for Wall Street and tax-funded stimulus bills, and then credibly complain about the “avalanche of new rules, restrictions, mandates and taxes” that may destroy the free enterprise system.

Posted on October 13, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Whole Milk and Humility

Dr. Melik: This morning for breakfast he requested something called “wheat germ, organic honey and tiger’s milk.”

Dr. Aragon: [chuckling] Oh, yes. Those are the charmed substances that some years ago were thought to contain life-preserving properties.

Dr. Melik: You mean there was no deep fat? No steak or cream pies or… hot fudge?

Dr. Aragon: Those were thought to be unhealthy… precisely the opposite of what we now know to be true.

Science hasn’t yet advanced as far as Woody Allen imagined in the movie Sleeper. But the Washington Post does report on its front page today, as the House Agriculture Committee holds a hearing on the government’s official Dietary Guidelines, that decades of government warnings about whole milk may have been in error.

In fact, research published in recent years indicates that the opposite might be true: millions might have been better off had they stuck with whole milk.

Scientists who tallied diet and health records for several thousand patients over ten years found, for example, that contrary to the government advice, people who consumed more milk fat had lower incidence of heart disease.

By warning people against full-fat dairy foods, the U.S. is “losing a huge opportunity for the prevention of disease,” said Marcia Otto, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Texas, and the lead author of large studies published in 2012 and 2013, which were funded by government and academic institutions, not the industry. “What we have learned over the last decade is that certain foods that are high in fat seem to be beneficial.”

The Post’s Peter Whoriskey notes that some scientists objected early on that a thin body of research was being turned into dogma:

“The vibrant certainty of scientists claiming to be authorities on these matters is disturbing,” George V. Mann, a biochemist at Vanderbilt’s med school wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine [in 1977].

Ambitious scientists and food companies, he said, had “transformed [a] fragile hypothesis into treatment dogma.”

And not just dogma but also government pressure, official Dietary Guidelines, food labeling regulations, government support for particular lines of research, bans on whole milk in school lunches, taxes and regulations to crack down on saturated fats and then on trans fats and salt. Earlier today Walter Olson noted numerous past examples of bad government advice on nutrition.

It’s understandable that some scientific studies turn out to be wrong. Science is a process of trial and error, hypothesis and testing. Some studies are bad, some turn out to have missed complicating factors, some just point in the wrong direction. I have no criticism of scientists’ efforts to find evidence about good nutrition and to report what they (think they) have learned. My concern is that we not use government coercion to tip the scales either in research or in actual bans and mandates and Official Science. Let scientists conduct research, let other scientists examine it, let journalists report it, let doctors give us advice. But let’s keep nutrition – and much else – in the realm of persuasion, not force. First, because it’s wrong to use force against peaceful people, and second, because we might be wrong.

This last point reflects the humility that is an essential part of the libertarian worldview. As I wrote in The Libertarian Mind:

Libertarians are sometimes criticized for being too “extreme,” for having a “dogmatic” view of the role of government. In fact, their firm commitment to the full protection of individual rights and a strictly limited government reflects their fundamental humility. One reason to oppose the establishment of religion or any other morality is that we recognize the very real possibility that our own views may be wrong. Libertarians support a free market and widely dispersed property ownership because they know that the odds of a monopolist finding a great new advance for civilization are slim. Hayek stressed the crucial significance of human ignorance throughout his work. In The Constitution of Liberty, he wrote, “The case for individual freedom rests chiefly on the recognition of the inevitable ignorance of all of us concerning a great many of the factors on which the achievement of our ends and welfare depends…. Liberty is essential in order to leave room for the unforeseeable and unpredictable.” The nineteenth-century American libertarian Lillian Harman, rejecting state control of marriage and family, wrote in Liberty in 1895, “If I should be able to bring the entire world to live exactly as I live at present, what would that avail me in ten years, when as I hope, I shall have a broader knowledge of life, and my life therefore probably changed?” Ignorance, humility, toleration—not exactly a ringing battle cry, but an important argument for limiting the role of coercion in society.

Today’s scientific hypotheses may be wrong. Better, then, not to make them law.

Posted on October 7, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

David Boaz discusses his blog post “Still the Slowest Recovery” on WTN’s Nashville’s Morning News

Posted on October 6, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty

Still the Slowest Recovery

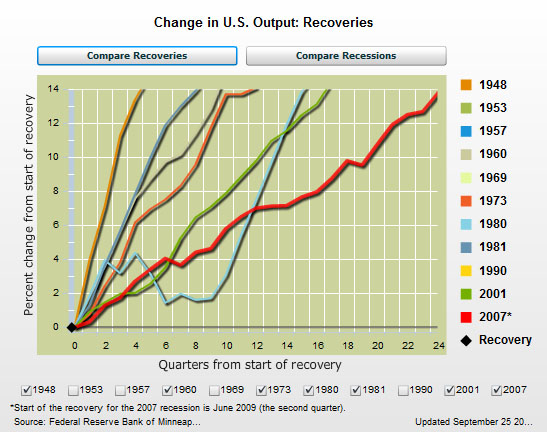

Friday’s disappointing jobs report reminds us that we are still in a very slow recovery from the 2007 recession. Not only were far fewer jobs created in September than economists predicted, the estimates for July and August were revised downward. And the size of the total workforce slipped to 62.4 percent of the population, the lowest level since 1977.

The Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank has a handy tool for monitoring the depressing news, allowing you to compare this recovery to past recoveries since World War II. Output (GDP) is recovering more slowly than in past recoveries, along with employment:

Why is the recovery so slow? John Cochrane of the Hoover Institution examined that question in the Wall Street Journal a year ago. Here’s part of his answer:

Where, instead, are the problems? John Taylor, Stanford’s Nick Bloom and Chicago Booth’s Steve Davis see the uncertainty induced by seat-of-the-pants policy at fault. Who wants to hire, lend or invest when the next stroke of the presidential pen or Justice Department witch hunt can undo all the hard work? Ed Prescott emphasizes large distorting taxes and intrusive regulations. The University of Chicago’s Casey Mulligan deconstructs the unintended disincentives of social programs. And so forth. These problems did not cause the recession. But they are worse now, and they can impede recovery and retard growth.

If you put obstacles in the way of investment and employment, you’ll likely get less investment and employment.

A new e-book edited by Brink Lindsey, Reviving Economic Growth, presents ideas from 51 economists of widely varying perspectives on this crucial question.

Posted on October 5, 2015 Posted to Cato@Liberty